Animal Farm: Allegory Explained + Character Analysis

| Difficulty Level: ★★★☆☆ (Moderate) |

|---|

| Language complexity: Clear, accessible prose suitable for high school level Structure: Straightforward chronological narrative with clear chapter divisions Themes: Sophisticated political concepts requiring historical context understanding Cultural/historical context: Requires knowledge of Russian Revolution and Soviet history Allegorical density: Rich symbolism requires analysis of character and event parallels |

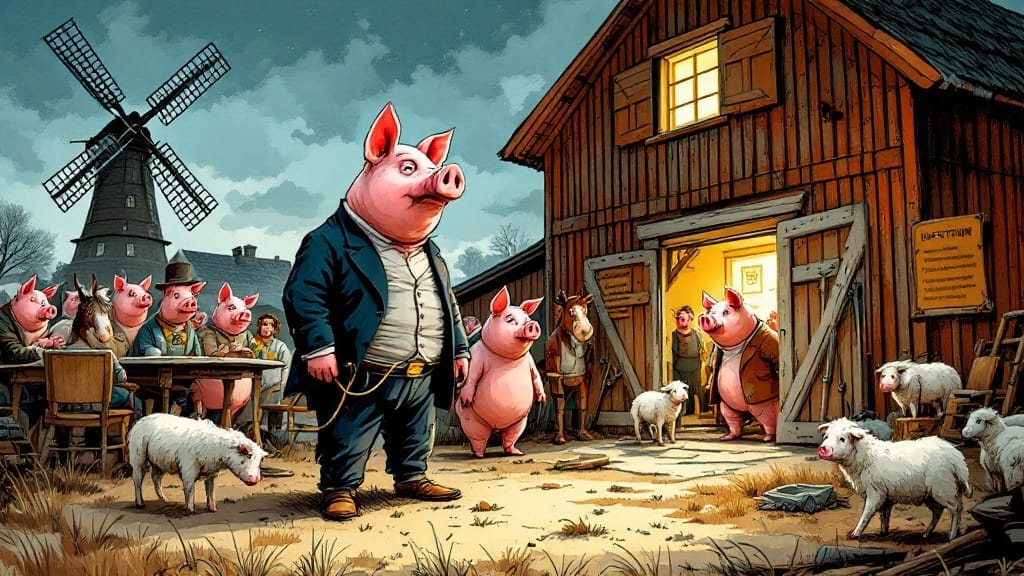

What if a single moment watching a young boy whip a cart horse sparked the creation of literature’s most famous political allegory? This deceptively simple tale of rebellious farm animals masks George Orwell’s sophisticated critique of the Russian Revolution and Stalin’s totalitarian regime. In just 92 pages, Orwell crafted characters whose symbolism and themes continue to define how we understand political manipulation and the corruption of revolutionary ideals.

Quick Reference Guide

| Basic Information | |

|---|---|

| Title | Animal Farm: A Fairy Story |

| Author | George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair) |

| Publication Date | August 17, 1945 |

| Genre | Political allegory, satirical fable, beast fable |

| Pages | 92 pages (original UK edition) |

| One-Paragraph Synopsis |

|---|

| George Orwell’s Animal Farm follows the animals of Manor Farm who rebel against their human owner, hoping to create an equal society where animals can be free and happy. Led by the pigs Napoleon and Snowball, they establish Animal Farm based on the principles of “Animalism.” However, the revolution gradually becomes corrupted as Napoleon seizes total power, betrays the farm’s founding ideals, and transforms into the very tyranny the animals originally fought against. This allegory mirrors the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the rise of Stalin’s totalitarian regime. |

| Key Characters | Role & Description |

|---|---|

| Napoleon | Berkshire boar representing Joseph Stalin; ruthless leader who corrupts the revolution through propaganda and violence |

| Snowball | Pig representing Leon Trotsky; intelligent revolutionary expelled by Napoleon to consolidate power |

| Boxer | Cart-horse representing the working class; loyal, hardworking, with mottos “I will work harder” and “Napoleon is always right” |

| Squealer | Pig representing Soviet propaganda; uses language manipulation to justify Napoleon’s increasingly corrupt actions |

| Old Major | Prize-winning boar representing Karl Marx/Lenin; inspires the rebellion with his vision of animal equality |

| Benjamin | Donkey representing cynical intellectuals; can read but remains pessimistic about the revolution’s outcomes |

| Mr. Jones | Human farmer representing Tsar Nicholas II; overthrown in the initial rebellion |

| Setting | |

|---|---|

| Time | Mid-20th century England (allegorically representing 1917-1940s Russia) |

| Place | Manor Farm (later renamed Animal Farm), representing Russia/Soviet Union |

| Key Themes at a Glance |

|---|

| • Corruption of Power – How revolutionary ideals become corrupted by those who gain authority • Totalitarianism – The development of oppressive political control through propaganda and fear • Class Warfare – The exploitation of working classes by new ruling elites • Language as Manipulation – How words are twisted to control and deceive populations • Failed Revolution – The tragic pattern of revolutions betraying their original principles |

| Reading Time Estimate |

|---|

| Casual reading: 3-4 hours Study reading with notes: 6-8 hours Exam preparation: 10-12 hours including analysis and context research |

Animal Farm Plot Summary & Allegorical Structure

Understanding George Orwell’s Animal Farm requires recognizing how its deceptively simple plot functions as a sophisticated political allegory. The novella’s structure follows the classical tragedy pattern, moving from initial hope through gradual corruption to final disillusionment, perfectly mirroring the arc of the Russian Revolution from 1917 to the Stalinist era (Orwell, 1945).

The Revolutionary Foundation: Chapters 1-2

The opening chapters establish the allegorical framework that transforms farmyard rebellion into revolutionary history. Old Major’s dream serves as both Marx’s Communist Manifesto and Lenin’s revolutionary vision, presenting the animals with a critique of their exploitation and a utopian alternative. Orwell’s genius lies in how he makes the animals’ grievances universally recognizable while maintaining specific historical parallels.

Critical Tension: Idealism vs. Reality The novella’s first structural paradox emerges immediately: Old Major delivers his revolutionary speech from an elevated platform, suggesting that even in advocating equality, hierarchies already exist. This foreshadowing technique demonstrates Orwell’s sophisticated understanding that corruption often begins within revolutionary movements themselves, not just through external corruption.

| Historical Event | Animal Farm Parallel | Analytical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Marx’s Communist Manifesto | Old Major’s speech about animal exploitation | Establishes ideological foundation while foreshadowing its corruption |

| February 1917 Revolution | Rebellion against Mr. Jones | Shows how genuine grievances can justify revolution |

| Initial Bolshevik success | Animals’ early prosperity under Animalism | Demonstrates that revolutionary ideals can initially work |

The Power Struggle: Chapters 3-5

These central chapters reveal Orwell’s most sophisticated political analysis: how revolutionary coalitions inevitably fracture along lines of personality and ideology. The Napoleon-Snowball conflict represents more than just Stalin versus Trotsky; it demonstrates the fundamental tension between pragmatic authoritarianism and idealistic internationalism.

Literary Technique Analysis: Dramatic Irony Orwell employs dramatic irony masterfully here—while the animals celebrate their freedom, readers recognize the signs of emerging tyranny. The pigs’ appropriation of milk and apples appears minor but establishes the crucial pattern of incremental corruption that will define the remainder of the narrative.

Examiner Insight: Top-scoring responses recognize that the windmill debate represents competing visions of communist society—Trotsky’s permanent revolution (Snowball’s international rebellion) versus Stalin’s socialism in one country (Napoleon’s fortress mentality).

The Consolidation of Power: Chapters 6-8

The novella’s middle section demonstrates Orwell’s understanding of how totalitarian control develops through manufactured crises and historical revisionism. Napoleon’s rise follows the classic pattern of authoritarian consolidation: eliminate rivals, create external enemies, and rewrite history to justify present actions.

Structural Analysis: Circular Narrative Orwell structures these chapters around repeating cycles of crisis and resolution, each one strengthening Napoleon’s position. The windmill’s destruction and reconstruction becomes a metaphor for how totalitarian leaders use grand projects to distract from systemic failures.

The Complete Transformation: Chapters 9-10

The final chapters complete Orwell’s allegorical circle, showing how revolutionary societies can become indistinguishable from what they originally opposed. The famous final scene—where animals cannot tell pigs from humans—represents one of literature’s most powerful expressions of political betrayal.

Critical Perspectives on the Ending

Contemporary scholars debate whether Orwell intended the ending as inevitable or preventable. This critical disagreement demonstrates the novella’s continued relevance to political theory and the complexity of Orwell’s political vision.

Animal Farm Character Analysis as Historical Allegory

Orwell’s characters function simultaneously as believable farm animals and precise historical allegories, creating what has been described as highly successful political satire. Understanding these dual layers requires analyzing both individual character development and collective symbolic meaning.

Napoleon: Stalin and the Corruption of Revolutionary Leadership

Napoleon embodies Orwell’s most sophisticated character creation—a figure who represents not just Stalin personally, but the general pattern of how revolutionary leaders betray their movements. His character development follows a deliberate arc from seeming equality to obvious superiority to indistinguishable tyranny.

Character Development Analysis

| Stage | Napoleon’s Actions | Historical Parallel | Literary Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Revolution | Works alongside other pigs | Stalin’s initial cooperation with Lenin | Establishes Napoleon as seemingly ordinary leader |

| Power Consolidation | Uses dogs to expel Snowball | Stalin’s elimination of Trotsky | Shows transition from ideological to personal conflict |

| Full Tyranny | Walks on hind legs, wears clothes | Stalin’s adoption of traditional power symbols | Completes allegorical circle of revolutionary betrayal |

Critical Analysis: The Paradox of Necessary Leadership Napoleon’s character raises uncomfortable questions about revolutionary leadership that extend beyond simple Stalin criticism. Orwell suggests that effective revolution requires strong leadership, but strong leaders inevitably corrupt revolutionary ideals—a paradox that has no simple resolution.

Snowball: Trotsky and the Tragedy of Idealistic Revolution

Snowball represents what literary critics call “unfulfilled revolutionary potential”—the intellectual idealist whose vision remains pure precisely because he never gains complete power. His character embodies the tragic tension between theoretical brilliance and practical politics.

Linguistic Analysis: Snowball’s Rhetoric Orwell carefully constructs Snowball’s language to reflect Trotsky’s intellectual sophistication and international perspective. His speeches about education and international revolution contain genuine insight, yet also reveal the kind of abstract theorizing that Napoleon can exploit as impractical.

Quote Bank for Analysis: “The only good human being is a dead one” reveals Snowball’s ideological extremism, while his windmill plans show practical intelligence—this contradiction makes him simultaneously sympathetic and dangerous.

Boxer: The Working Class and the Tragedy of Misplaced Loyalty

Boxer’s character represents Orwell’s most emotionally complex creation—a figure who embodies the working class’s greatest strengths (loyalty, hard work, physical power) and most dangerous weaknesses (unquestioning obedience, intellectual passivity).

Symbolic Density Analysis Boxer functions as multiple symbols simultaneously: the Russian proletariat, the Stakhanovite movement, and universal working-class experience. His famous mottos—”I will work harder” and “Napoleon is always right”—demonstrate how noble impulses become tools of oppression when combined with intellectual powerlessness.

Critical Tension: Strength vs. Vulnerability The paradox of Boxer’s character lies in how his greatest asset (physical strength) becomes meaningless against intellectual manipulation. When he questions Napoleon’s revision of historical events, his physical power briefly threatens the pigs’ authority, but his intellectual submission ultimately ensures his destruction.

Squealer: Propaganda and the Weaponization of Language

Squealer embodies Orwell’s sophisticated understanding of how language becomes a tool of political control. His character represents not just Soviet propaganda specifically, but the universal tendency of political systems to manipulate truth through rhetorical skill.

Rhetorical Technique Analysis Squealer employs specific propaganda techniques that mirror real totalitarian practice: euphemism (calling exploitation “sacrifice”), false statistics (claiming production increases during obvious decline), and historical revisionism (rewriting Snowball’s role in the Battle of the Cowshed).

Dialectical Function in the Novel Squealer serves as the essential bridge between Napoleon’s actions and the animals’ acceptance. Without his linguistic manipulation, Napoleon’s tyranny would be obvious; with it, oppression becomes justified. This demonstrates Orwell’s insight that successful tyranny requires active intellectual participation, not just passive submission.

Animal Farm Themes Analysis: Power, Propaganda & Corruption

Orwell’s thematic exploration transcends simple anti-Soviet polemic to examine universal patterns of political behavior that remain relevant across historical contexts. The novella’s themes operate in dialectical tension with each other, creating complex meanings that resist simplistic interpretation.

The Corruption of Power: Beyond Simple Maxims

While often reduced to “power corrupts,” Orwell’s analysis of power corruption operates at multiple levels of sophistication. The novella demonstrates that corruption begins not when leaders gain power, but when they begin to see themselves as essentially different from those they govern.

Structural Pattern of Corruption

- Initial Equality: All animals work together in genuine cooperation

- Justified Privilege: Pigs claim special treatment for intellectual work

- Expanded Privilege: Benefits extend beyond necessity to comfort

- Open Tyranny: Pigs abandon all pretense of equality

- Complete Transformation: Revolutionary leaders become indistinguishable from original oppressors

Critical Perspective: The Inevitability Debate Scholars debate whether Orwell presents corruption as inevitable within hierarchical systems or explores specific failures rather than universal truths. This scholarly disagreement reflects the text’s deliberate ambiguity about whether political corruption represents human nature or systemic failure.

Language as Political Weapon: The Squealer Phenomenon

Orwell’s exploration of linguistic manipulation anticipates his later development of “Newspeak” in 1984, but Animal Farm focuses more specifically on how rhetoric transforms meaning while appearing to preserve it.

Linguistic Manipulation Techniques

| Technique | Example from Text | Real-World Parallel | Effect on Animals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euphemism | “Readjustment” instead of “reduction” | Soviet terminology for rationing | Disguises harsh reality |

| False Statistics | Claims of increased egg production | Stalinist propaganda about Five-Year Plans | Creates illusion of progress |

| Historical Revision | Rewriting Snowball’s role at Cowshed | Stalin’s erasure of Trotsky from history | Controls collective memory |

| Logical Fallacy | “All animals are equal, but some are more equal” | Doublethink in totalitarian systems | Normalizes contradiction |

The Paradox of Revolutionary Language The novella explores how revolutionary movements inevitably face a linguistic paradox: they must use existing language to describe new realities, but existing language carries old assumptions about power and hierarchy. The pigs’ corruption begins linguistically before it becomes behavioral.

Class Struggle and the Failure of Solidarity

Orwell’s analysis of class dynamics reveals sophisticated understanding of how revolutionary movements fragment along lines of education, function, and capability rather than simple economic interest.

Class Stratification Analysis

- Intellectual Elite (Pigs): Claim authority through education and planning capability

- Skilled Labor (Dogs): Gain privilege through specialized function (violence)

- Productive Labor (Boxer, Clover): Provide economic foundation but lack political power

- Marginal Elements (Benjamin, Mollie): Remain outside revolutionary commitment

Critical Insight: The Education Problem The novella suggests that educational inequality makes democratic revolution impossible—the educated inevitably exploit their advantage over the uneducated. Yet without education, the working class cannot effectively challenge manipulation. This represents what scholars call “Orwell’s democratic dilemma.”

Animal Farm Historical Context & Political Background

Understanding Animal Farm‘s historical context requires recognizing how Orwell’s personal experience of Stalinist persecution during the Spanish Civil War shaped his specific critique of Soviet communism while maintaining broader applicability to totalitarian systems generally (Orwell, 1938).

The Russian Revolution: From February to October 1917

The historical foundation of Animal Farm rests on Orwell’s interpretation of how the Russian Revolution’s democratic phase gave way to Bolshevik authoritarianism. Manor Farm’s transformation parallels Russia’s movement from tsarist autocracy through provisional government to Soviet state.

Revolution Timeline and Allegorical Parallels

| Historical Event | Date | Animal Farm Parallel | Orwell’s Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| February Revolution | Feb 1917 | Mr. Jones’s initial expulsion | Justified popular uprising against incompetent autocracy |

| Provisional Government | Mar-Oct 1917 | Early collective leadership | Democratic ideals undermined by practical pressures |

| October Revolution | Oct 1917 | Pigs’ assumption of leadership | Intellectual elite exploits popular revolution |

| Lenin’s Death | 1924 | Old Major’s death | Power vacuum enables opportunistic succession |

| Stalin-Trotsky Struggle | 1924-1929 | Napoleon-Snowball conflict | Personal ambition destroys ideological unity |

Stalinism and the Corruption of Socialist Ideals

Orwell’s critique targets not socialism itself but its corruption under Stalin’s totalitarian system. The novella explores how genuine socialist principles—collective ownership, worker control, egalitarian distribution—become rhetorical tools for maintaining oppression.

Stalin’s Methods and Napoleon’s Parallels

- Collective Agriculture: Forced collectivization parallels the windmill project’s prioritization over food production

- Show Trials: Public confessions and executions mirror the animals’ forced confessions and deaths

- Cult of Personality: Stalin’s image cultivation parallels Napoleon’s growing ceremony and ritual

- Historical Revision: Trotsky’s erasure from history parallels Snowball’s transformation into a traitor

Critical Analysis: Democratic Socialist Perspective Orwell wrote as a democratic socialist who supported collective ownership while opposing authoritarian implementation. This position allows him to critique Soviet practice without rejecting socialist theory—a nuanced stance often overlooked in simplified readings of the text.

The Spanish Civil War: Orwell’s Formative Experience

Orwell’s participation in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) provided direct experience of how Stalinist forces suppressed other leftist groups, shaping his understanding of how revolutionary movements consume their own supporters.

Barcelona May Days Influence During the Barcelona May Days conflicts, Orwell witnessed POUM (anti-Stalinist) forces being eliminated by Soviet-directed communists despite their shared opposition to fascism. This experience taught him that ideological purity becomes a weapon against practical solidarity—a theme central to Animal Farm‘s exploration of revolutionary betrayal.

Publication Challenges and Political Climate

The novella’s publication in 1945 occurred during the transition from wartime alliance to Cold War opposition between Britain/America and the Soviet Union. Multiple publishers initially rejected Animal Farm because criticizing the Soviet Union seemed problematic during wartime alliance.

Reception and Political Use Once the Cold War began, the novella’s anti-Soviet message aligned with Western political needs. The work’s subsequent prominence in cultural diplomacy demonstrates how Orwell’s complex political critique could be simplified for ideological purposes—ironically validating his warnings about propaganda’s power to manipulate meaning.

Orwell’s Literary Techniques in Animal Farm Analysis

George Orwell’s technical mastery in Animal Farm lies in his ability to create multiple layers of meaning while maintaining narrative accessibility. His literary techniques serve the dual purpose of engaging general readers and providing sophisticated political analysis for those equipped to recognize it.

Allegorical Construction: The Beast Fable Tradition

Orwell’s choice of animal allegory draws on the beast fable tradition while subverting its conventional moral simplicity. Unlike Aesop’s fables, which present clear moral lessons, Animal Farm uses animal characteristics to explore political complexity rather than moral certainty.

Character-Species Matching Analysis

- Pigs: Intelligence without morality, paralleling intellectual class corruption

- Horses: Physical strength with emotional nobility, representing working class virtue and vulnerability

- Dogs: Loyalty transformed into violence, showing how protective instincts become oppressive tools

- Sheep: Mindless repetition, representing mass manipulation and mob behavior

- Ravens: Superstition and false comfort, symbolizing organized religion’s political function

Critical Technique: Anthropomorphic Paradox Orwell creates deliberate tension between animal nature and human behavior. The pigs’ adoption of human traits (walking upright, wearing clothes) becomes horrifying precisely because it violates the natural order established earlier in the narrative. This technique makes political corruption seem both inevitable and deeply unnatural.

Satirical Strategy: Swiftian Social Criticism

Following Jonathan Swift’s satirical model, Orwell uses apparently innocent content to deliver devastating political criticism. The novella’s subtitle—”A Fairy Story”—signals this satirical intent while protecting the work from direct political suppression.

Satirical Techniques in Operation

| Technique | Application | Effect | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ironic Understatement | Describing atrocities in calm language | Makes horror more disturbing through contrast | “It was a few days later than this that the pigs came upon a case of whisky” |

| Mock-Heroic Treatment | Treating trivial events with epic language | Reveals absurdity of totalitarian pomposity | Napoleon’s elaborate titles and ceremonies |

| Logical Reduction | Following principles to absurd conclusions | Exposes contradictions in political rhetoric | “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others” |

Structural Irony: Circular Narrative Pattern

The novella’s structure creates meaning through pattern recognition rather than linear development. The return to human-animal convergence in the final scene completes a circle that suggests historical repetition rather than progress.

Circular Structure Analysis

- Opening State: Animals oppressed by humans

- Revolutionary Phase: Animals achieve temporary equality

- Corruption Phase: New leaders gradually adopt old patterns

- Final State: Animals again oppressed, but by their own kind

- Closing Recognition: No essential difference between oppressors

This circular structure supports Orwell’s pessimistic view that political revolutions tend to reproduce rather than eliminate oppressive patterns, while leaving open the possibility that recognition itself might enable different outcomes.

Language Analysis: Plain Style and Political Purpose

Orwell’s deliberately plain prose style serves his political purpose by making complex ideas accessible while avoiding the linguistic manipulation he criticizes. His essay “Politics and the English Language” outlines principles directly applied in Animal Farm (Orwell, 1946).

Prose Style Characteristics

- Concrete Language: Specific details rather than abstract concepts

- Active Voice: Clear attribution of responsibility for actions

- Simple Sentence Structure: Accessibility across education levels

- Minimal Metaphor: Direct statement rather than decorative language

Critical Insight: Style as Political Statement Orwell’s plain style becomes a political argument against the obfuscation and manipulation demonstrated by Squealer’s rhetoric. By writing clearly about propaganda’s effects, Orwell models the kind of honest communication necessary for democratic discourse.

Foreshadowing and Dramatic Irony: Reader Participation

Orwell constructs the narrative to make readers collaborators in recognizing patterns that the characters miss. This technique transforms reading into a form of political education about recognizing authoritarian development.

Foreshadowing Network

- Chapter 1: Old Major’s elevated platform foreshadows pig hierarchy

- Chapter 3: Milk and apple appropriation foreshadows complete privilege

- Chapter 5: Napoleon’s dog training foreshadows violent oppression

- Chapter 7: Show trials foreshadow complete totalitarian control

Reader Positioning Strategy By providing readers with information unavailable to characters, Orwell creates a parallel between reading the novella and observing political situations in real life. The skills required to recognize foreshadowing become analogous to the skills needed to identify emerging authoritarianism before it becomes obvious.

Critical Analysis & Key Passages

Analyzing specific passages from Animal Farm reveals how Orwell’s technical mastery creates layers of meaning that operate simultaneously as surface narrative, historical allegory, and universal political commentary. These close readings demonstrate the analytical techniques necessary for sophisticated literary examination.

Passage Analysis 1: Old Major’s Speech (Chapter 1)

“Now, comrades, what is the nature of this life of ours? Let us face it: our lives are miserable, laborious, and short. We are born, we are given just so much food as will keep the breath in our bodies, and those of us who are capable of it are forced to work to the last atom of our strength; and the very instant that our usefulness has come to an end we are slaughtered with hideous cruelty.”

Literary Technique Analysis This passage employs rhetorical parallelism (“we are born, we are given, we are forced”) to create rhythmic emphasis while establishing the revolutionary foundation. The progression from birth to death creates inevitability that justifies rebellion while the concrete imagery (“last atom of our strength”) makes abstract exploitation tangible.

Allegorical Significance The speech functions as both Marx’s analysis of capitalist exploitation and Lenin’s call for revolutionary consciousness. The economic critique (labor extraction until death) parallels Das Kapital, while the emotional appeal (“comrades”) reflects Bolshevik organizing strategy.

Critical Complexity The passage’s power lies in its genuine insight into exploitation combined with foreshadowing of future corruption. Old Major’s elevated platform and assumption of natural leadership reveal hierarchical tendencies within supposedly egalitarian movements—a subtle warning about revolutionary leadership that becomes explicit later.

Passage Analysis 2: The Seven Commandments (Chapter 2)

“1. Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy. 2. Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend. 3. No animal shall wear clothes. 4. No animal shall sleep in a bed. 5. No animal shall drink alcohol. 6. No animal shall kill any other animal. 7. All animals are equal.”

Structural Analysis The commandments’ structure moves from external identification (enemies/friends) through behavioral restrictions to fundamental principle. This progression reflects how revolutionary movements typically prioritize immediate threats before establishing positive principles—a historically accurate insight into revolutionary development.

Language as Power Theme The commandments’ subsequent modification demonstrates Orwell’s sophisticated understanding of how political language functions. Each alteration preserves surface meaning while destroying essential content: “No animal shall kill any other animal without cause” maintains the prohibition while creating the exception that destroys it.

Examiner Insight Box

Advanced Analysis Technique: Notice how the commandments progress from specific prohibitions to general principle. This structure makes the final commandment most vulnerable to interpretation—exactly what enables its later corruption. Strong analytical responses recognize this structural vulnerability as deliberate authorial choice.

Passage Analysis 3: Napoleon’s Transformation (Chapter 10)

“The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

Symbolic Culmination This final sentence completes the allegorical circle while operating as social commentary beyond its Soviet context. The inability to distinguish oppressor from oppressed leader suggests universal patterns of revolutionary betrayal rather than specifically Russian failure.

Technical Mastery: Chiasmic Structure The sentence’s chiasmic pattern (A-B-A structure) creates symmetry that emphasizes equivalence while the repetition (“from pig to man, and from man to pig”) mirrors the cyclical historical pattern the entire novella describes. This structural parallel between sentence and narrative demonstrates Orwell’s technical sophistication.

Multiple Critical Perspectives

- Pessimistic Reading: Revolutionary change always leads to restored oppression

- Optimistic Reading: Recognition enables different choices in future situations

- Historical Reading: Soviet communism specifically betrayed its principles

- Universal Reading: All political systems tend toward elite self-interest

Passage Analysis 4: Boxer’s Betrayal (Chapter 9)

“It was a few minutes before Boxer could rest, for the van had started and was gathering speed. His face disappeared from the window and was seen no more. It was a few days later that the pigs announced that Boxer had died in the hospital in Willingdon, despite receiving every care that could be given to a sick horse.”

Tragic Technique: Understated Horror Orwell’s deliberately flat narration makes Boxer’s betrayal more horrific than dramatic description would achieve. The contrast between narrative calm and character destruction forces readers to experience the emotional impact independently—a technique that parallels how totalitarian systems normalize atrocity through bureaucratic language.

Class Analysis Framework Boxer represents the working class’s tragic relationship to revolutionary movements: providing essential support while remaining vulnerable to betrayal. His literal value (sold for slaughter) parallels the metaphorical expendability of working-class supporters once their usefulness ends.

Historical Parallel Recognition The passage allegorizes Stalin’s treatment of Old Bolsheviks and revolutionary supporters—eliminated once they served their purpose but potentially inconvenient to new directions. The hospital lie parallels Soviet disinformation about political prisoners’ fates.

Quote Bank for Essays: This passage demonstrates how revolutionary movements often consume their most loyal supporters, making it essential for analyzing themes of betrayal, class exploitation, and the tragic irony of revolutionary participation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Animal Farm About?

Animal Farm tells the story of farm animals who rebel against their human owner, hoping to create an equal society where animals can be free and happy. However, the rebellion is gradually corrupted by the pigs, led by Napoleon, who become as oppressive as the humans they overthrew. The novella serves as an allegory for the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the rise of Stalin’s totalitarian regime, showing how revolutionary ideals can be betrayed by those seeking power.

Who Does Napoleon Represent in Animal Farm?

Napoleon represents Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader who rose to power after Lenin’s death in 1924. Like Stalin, Napoleon eliminates his rivals (such as Snowball/Trotsky), uses propaganda and violence to maintain control, and gradually abandons revolutionary principles while claiming to act in the people’s interest. Napoleon’s character demonstrates how revolutionary leaders can become as tyrannical as the systems they originally opposed, reflecting Orwell’s critique of Stalin’s authoritarianism.

What Does the Windmill Symbolize in Animal Farm?

The windmill symbolizes both the promise of technological progress and the manipulation of popular hopes by political leaders. Initially representing the animals’ aspirations for improved living conditions and self-sufficiency, it becomes a tool for Napoleon’s control and propaganda. Its repeated destruction and reconstruction mirror Stalin’s Five-Year Plans and demonstrate how totalitarian leaders use grand projects to distract from systematic oppression while exploiting workers’ labor.

Why Did George Orwell Write Animal Farm?

Orwell wrote Animal Farm as a critique of Stalin’s Soviet Union and totalitarianism in general. Having witnessed Stalinist suppression of other leftist groups during the Spanish Civil War, Orwell wanted to expose how revolutionary movements could be corrupted by power-seeking leaders. As he stated in his 1946 essay “Why I Write,” he intended to “fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole” (Orwell, 1946).

What Does “All Animals Are Equal, But Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others” Mean?

This famous quote represents the ultimate corruption of revolutionary ideals through linguistic manipulation. It demonstrates how those in power twist language to justify inequality while appearing to maintain original principles. The phrase’s logical contradiction mirrors how totalitarian regimes use doublethink to normalize oppression, showing that when language becomes a weapon of political control, truth itself becomes meaningless and tyranny becomes acceptable.

Who Does Boxer Represent in Animal Farm?

Boxer represents the working class and specifically the Soviet proletariat who supported the revolution through physical labor and unwavering loyalty. His mottos “I will work harder” and “Napoleon is always right” embody the working class’s noble dedication but also their vulnerability to exploitation by intellectual elites. Boxer’s tragic fate—being sold to the knacker despite his loyalty—demonstrates how revolutionary movements often consume their most faithful supporters once they’re no longer useful.

What Does Benjamin the Donkey Represent?

Benjamin represents cynical intellectuals or older citizens who remain skeptical of political change, believing that “life will go on as it has always gone on—that is, badly.” He symbolizes those who possess the ability to recognize corruption (he can read and remembers the original commandments) but choose not to act until it’s too late. Benjamin’s character warns against intellectual passivity and the dangers of remaining silent in the face of growing tyranny.

What Are the Seven Commandments and Why Do They Change?

The Seven Commandments represent the original principles of Animalism (communism), establishing equality among animals and prohibiting human-like behaviors. They change because the pigs gradually modify them to justify their increasing privileges and power. Each alteration maintains surface meaning while destroying essential content, demonstrating how political language becomes a tool for legitimizing oppression. The commandments’ corruption shows how revolutionary principles are systematically betrayed by those claiming to uphold them.

What Does Old Major’s Speech Represent?

Old Major’s speech represents the ideological foundation of revolutionary movements, specifically combining Karl Marx’s analysis of capitalist exploitation with Lenin’s call for revolutionary action. The speech successfully identifies genuine grievances (the animals’ exploitation) and presents a vision of liberation, but it also reveals hierarchical tendencies that foreshadow future corruption. Old Major’s elevated platform during the speech subtly suggests that revolutionary leadership itself contains the seeds of inequality that will ultimately destroy the revolution’s egalitarian goals.

References

• Orwell, G. (1938). Homage to Catalonia. Secker & Warburg.

• Orwell, G. (1945). Animal Farm: A fairy story. Secker & Warburg.

• Orwell, G. (1946). Why I write. Gangrel, 4, 5-10.